Southwell Minster

Every Cathedral wants to have it’s "thing”, they want to be the biggest, the oldest, the most visited. They have to be the longest, the widest, the tallest. For some, that’s simple, for others… less so. There’s 42 Church of England Cathedrals alone, let alone all the other denominations, and so you soon run out of things they can be the biggest or best at.

This is why, when I visited Southwell Minster, the Priest I was with took me to the arched gateway to the west of the Cathedral, pointed down the long path towards the west doors, and said: “Southwell has the longest bridal walk of any Cathedral in England. It’s the longest distance from the car, pulled up here, to the altar inside.” I said “You know that’s not a thing, right?”, he said “… yeah… But we’ve got to have something.”

Luckily for him, on this visit Southwell broke two of my own personal records, the one for “most dead birds found on a single staircase” AND “most dead birds found on a tower climb” (these things are related). I don’t think they’ll be putting that on the advertising materials though.

Anyway, that’s enough about dead birds (for now), let’s get into it, shall we?

Southwell is a gloriously chunky old girl sited, oddly for a Cathedral, in a small town (not city) of around seven or eight thousand people. There’s no obvious reason for the Cathedral to be here, until you get to the Cathedral itself. Beside it, the ruins of an enormous structure enclose the modern day Bishop’s Palace. This used to be the palace of the Archbishop of York, sat, here, in his most southerly diocese. A symbol of great power, and control.

All that remains standing is part of the hall. This area is now used as a multi-purpose events space, for talks, meetings, dinners, etc. As part of the palace, however, this room would likely have been the space where Cardinal Wolsey held negotiations in an attempt to save himself from arrest and ruin at the hands of King Henry VIII, and is widely believed to be the place in which King Charles I was arrested, before being transported to his place of imprisonment.

But we’re here for the Cathedral, not the Bishop’s Palace. So, let’s take a look at what we’re in for.

A walk around the exterior gives a sense of the place.

Southwell sits on the site of an earlier Saxon church, but, in it’s current form, was mostly constructed between 1100’s and the 1150’s.

The way church and Cathedral construction often worked was that you’d build from east to west, so though construction on the cathedral we know today started in 1108, it began at the east end, which was demolished in a later scheme of rebuilding (which also ran east to west), in the 1200’s. This means the earliest substantial part of the Cathedral can be found where that new construction ended - at the base of the central tower - and dates to the 1120’s.

So let’s go inside. At the east end is the Gothic chancel, a great golden confection, the stone gleaming, and studded with great lancets of stained glass.

Here the decorations begin to hint at the decadence to be found in the famed Chapter House… but we’ll get there (at the end). For now, enjoy the symmetry of the elevations, those careful gothic points, counteracting the curves of the Romanesque nave.

Then, to the west, is that nave, built between 1120 and 1150, full of those tell-tale Romanesque semi-circles, and gorgeously chunky columns, marching all the way down to the west front, with it’s huge window, pouring light into the space.

But I see you looking, up, at the triforium, the clerestory, the ceiling. Shall we go? Shall we see what we can see?

Well, let us begin, as all good adventures begin, with a locked door, and a spiral staircase.

These stairs are in good condition, the wear has been levelled out, and there’s even fancy white lines for health and safety!

They lead, however, to this strange scramble up some metal rungs, and on to a catwalk, placed, carefully, on top of the pipework that made the old stone walkway impassable. This may all sound (and look) kind of sketchy, but for someone to put in so much work to enable access means this must lead somewhere people actually have reason to go.

Up the rungs, grab the railing for stability for a second there, and we’re stood in front of the north windows, looking across the the south transept. Between us and it, the great tower, arching boldly across the space, it’s vast piers holding up tonnes of stone and metal, and wood.

Behind us, contrasting the solidity and immovability of the stone, fragile glass windows swirl with lead patterns, and delicate painting, even up here, where no-one can see.

Following the transept along, we slip behind a column, turn a corner. There’s a door, up ahead, with a sign on it…

This is where they hide the inside of the organ, the blower, the mechanism which forces air through the pipes, producing that enormous sound! Organs are, after all, wind instruments.

Inside the room the blower is boxed away, but shows signs of being regularly maintained. This explains why the path here is so simple. But on the other side of it is another door, so let’s find out where it leads.

The route around to that door is treacherous, requiring a balancing act, feet carefully placed atop metal pipework. Clearly this part of the Cathedral is visited far less often…

Through that door, and there, above us, is the underside of the north east aisle roof! Here, huge wooden beams, braced into the stone, hold up the pitched roof.

Those strange pieces of white board on the right of the photo above block up the openings into the chancel, they’re fire proofing, and it’s really reassuring to see them in place (though they could, perhaps, have made the other side more appealing to look at). Southwell suffered a great fire after a lightning strike in 1711, which destroyed much of the roofs and ceilings to the western end of the building, and it clearly taught them a great lesson, namely, to take fire safety seriously.

Below our feet, the tops of the pointed aisle vaults lift up their humped stone backs, one after the other, undulating away into the distance.

At the east end, a single window peeks out behind the beams, trickling sunlight into the space, the cobwebs hanging from every surface, a reminder of how rarely this part of the Cathedral is entered.

As we return to the door there’s a hatch, outlined with daylight, a peek outside gives a glimpse of a beautiful flying buttress amidst the trickling rain.

This room is clearly a dead end. Let’s get back on the move. There’s only an hour or two before Evening Prayer, and there’s so much more to see!

First, we’ll get back onto that walkway, and inch our way over the pipes…

Don’t forget to look up, at the beauty of the North transept…

Then eyes back down, on that awkward walkway, because we’re going round the corner, into the nave itself. and you don’t want to trip on the way!

That’s the transept traversed safely, and we’re into the nave triforium. Here the great Romanesque arches run along one side of the passage, open to the air. Unlike some triforium levels, this one doesn’t have its own windows, so the light comes in from the direction of the nave itself, the columns to the south casting their shadows across the dusty floor.

Like many Cathedral organs, the one in Southwell sprawls, taking over all the space it can find. And here, stood over the north west aisle, you can look over, and see it filling the triforium on the opposite side, pipes framed and glistening between the arches.

Unlike the instrument-filled south side, the north side is filled with the accumulated junk of centuries. This is typical for an old church, most of which were built with almost no storage space, and have had to make the most of any hidden areas, no matter how high up or inaccessible they may be.

Here’s a painting… a sign…

a broken chair…

a scale model of the Minster itself…

We step along the wide passageway, taking note of random junk, until, among the detritus, a flight of steps, a hidden room…

Let’s explore!

Many old churches have these small rooms hidden above their north porches. They would have housed Clergy, and often contain blocked up fire places, and other remnants of domestic life. Nowadays they’re most often used as even more storage space.

There’s nothing of much note here, however, so out we go, further west, towards the famous pair of towers that soar up to flank the west end of the Cathedral.

In the tower itself the windows are plain glass, offering as much light as possible to the enclosed space.

As you would expect in a tower, the rooms are square, but at Southwell the walls are thick with passages, creating a gallery around almost every room.

There’s more hidden storage here, old nativity sets, thousand year old animal bones, crates of chaos, all awaiting the moment they are needed.

But we’re here for the climb… So up we go!

Outside the narrow windows of the staircase, that long bridal walk hazes into view through the grime and myriad bubbles in the glass.

As we go higher we pass the entrance to the ledge that runs between the towers, right in front of that vast west window.

Then up, up some more, into the galleries above that first storage room. Wonderfully, even here the columns have carved capitals.

The next room we come to is almost entirely empty. However, abandoned on the floor, are five stalls, made redundant by the creation of the Diocese of Derby in 1927. By the looks of them, they’ve been up here ever since.

Up here, the central tower peers through the east windows…

Let’s go and find it…

There’s a hatch, the size of a torso. Some rusted bolts. Then, we’re peering out…

There’s the central tower! Wave hello, we’ll be there soon!

And in front, the south west tower, the mirror of this one!

And as you can tell by the height of the south tower, rising above us, there’s still more climbing to be done!

By this point, we’ve already encountered a few dead pigeons on the stairs, it’s very hard to keep them out, and it’s usual to find one or two when climbing a rarely visited tower. Things are, however, about to get bad…

(If you want to avoid the dead bird part of this climb, click here)

We step back onto the staircase, gingerly, now, making our way past tiny corpses. At some points, it’s only my small feet, and experience with spiral staircases, that allows me to get through “There’s clearly an opening up here” I tell the guy I’m with “This is way more than usual!” I pause to text my friend, the ornithologist, asking how small a gap a pigeon needs to get into a building. He responds immediately, and it turns out the answer is “an extremely tiny one.”

We get to the next room. The tall windows slice up through the gloom.

There’s graffiti all over here. Clearly this was the last stop for many an illicit Cathedral climber, and once here, they felt the need to make their mark.

The views are wonderful, the light seemingly endless…

But this great ancient room, high up in the cathedral, is a tomb.

The guy I was with got out his radio, and called back down into the main body of the Cathedral: “Um… there’s a lot of dead birds in the north tower” “How many birds?” “… at least fourteen…”

It was a new record, for me, and not a pleasant one.

I suggested we look for the gap they were getting in through, no matter how small, and so we climbed higher, into the roof structure itself. It was pitch black up there, the stone steps soon ran out, my head crushed sideways against a roof beam. I clung to a chunk of wood, and tried to look around, but there was no light. No glimpse of the entry point. No way to know where the hole was, no way to stop the birds coming in. We turned on our phone torches, and their beams were swallowed by the nothingness. It was futile, especially on a day as overcast at this.

We descended, again, into the highest room of the tower. The smell wasn’t great. Nor was the situation. We descended, down the stairs, through the passageways, tiptoeing over the dead, unable to clear them away without the proper protective equipment. Their bodies, new and old, left to their unexpected and ancient mausoleum.

But back to the climb, and we’ve descended to the level of the cathedral proper. Here passages open up again, into the main body of the church.

First, the clerestory, the highest and and narrowest passage through the wall of the nave. I’m not allowed in there without a harness and certifications, as there’s nothing to stop you falling to an almost certain death. But by God I want to go some day. Take a peek, anyway…

Then down further, and further

Back into the triforium, and let’s glance back, at the glorious west window, lighting up more and more as the sun moves west towards its setting.

Heading back to the East now, towards the central tower…

There, across the transept from us, is the door to the aisle roof, the steps up to it seeming all the more precarious from this angle.

Back along the transept we go, across from us, the organ balances, atop the great carved rood screen. Above it, in the tower itself, more passages… shall we go?

Of course we’ll go! But we’ve got to get there!

Up, up, into the transept clerestory, from here the church stretches out below us, the people tiny and distant.

Even up here, the round windows still boast coloured glass and delicate lead patterns.

Some even open, if you’re brave (and really in need of a through breeze).

The stone, too, is detailed. Like we saw in the north west tower, even when hidden from human eyes, or almost impossible to see, the capitals are carved with care.

Some say that these old Romanesque cathedrals are dark, dank things, tombs or caves compared to later gothic buildings that were basically all windows, between thin spiderwebs of stone. But look around… from this lofty perch the green of the trees, magnified by the coloured glass, brings nature into this great place, through an inpouring of light.

Behind us, the hidden passage from whence we came. Spiral staircase glowing firey orange in the light of an incandescent bulb.

Ahead, another staircase. This one, with only a handful of steps, leads up to the tower.

The view from the crossing of the Cathedral is magnificent!

Up close like this, the fine details of the ancient carving sings. The light and shadow a shifting part of the art - and all the more beautiful because of the change.

Behind us, another door. Another lock. Another key. Then a scramble up a steep wooden ramp.

We’re standing above that great gothic chancel, now. Below our feet, the catwalk over the vaulted ceiling; above our heads, the great lead roof; to the west, the small entrance door.

The vaults are much larger than the ones in the aisles and continue, row after row, towards the east. There they meet a row of windows which let great gouts of light into the roof space. In any other building they’d be deemed “big”, but in a cathedral, they’re practically minuscule.

It’s always in the hidden spaces that you find the truth of a Cathedral, and here, too, this is true. For example, you can see, in this blocked up archway, where the 1200’s crashed, with full force, into the 1100’s; leaving only this strange and shattered cascade of stone.

The vaults themselves are neat and regular, and fireproofed. More evidence that the fire of 1711 has put appropriate amounts of fear into everyone here.

And now, back out, through the (fireproof) doorway, into that incredible crossing.

Let’s circle round a little. Take a peek at the south transept, framed between roof beams, each archway embellished with twisted, rope-like, stone.

There, too, is the south Transept, from whence we came, framed by the vast arch of the tower.

Then up, through another door, and into a small staircase, look out the window! There’s the north tower! We were just up there!

This staircase is clearly well used. A millennia of hands have polished the central column to a shine, and these days it even has a rope for a handle, carefully tied off, and well cared for.

It leads up to the ringing room, home to that strange breed of person, the bell ringer.

Like most ringing rooms, the walls are covered in plaques, celebrating successful feats of ringing, each many hours long, and comprised of complex mathematical patterns.

Like the North tower, the walls here are lined with passages, and my guide took me over to the west. “Look here” he said.

And the wall dropped open.

I wriggled through the gap. Nothing was going to stop me. How could I not go feral at a door as ridiculous as that? A vertical trapdoor, in a tower wall, that barely even opens because of the wall opposite! Incredible!

Slip through the door, let your eyes become accustomed to the darkness and the dim light trickling up from below… There’s a strange quality to the sound here. There’s noise, echoes, the space sounds bigger than it looks.

This is the space above the nave ceiling. A thin slatted walkway of wood, perched, precariously on the curved and widely spaced wooden beams of the barrel vault.

Below, the ceiling is open. And as we walk along, there are views between the beams, all the way down.

At the west end, the great window looms, a point of radiant light, drawing all who see it ever forwards, step by step, along the creaking walkway above the nave.

Finally, the walkway runs out, and there, filling the space before us, and illumed by the evening light, is a great and radiant wall of angels.

This window dates from 1996, was conceived by Martin Stancliffe, painted by Patrick Reyntiens and crafted by Barley Studios in York, and replaces some Victorian stained glass.

As well as being utterly beautiful, the window is innovative. It’s actually created with two layers of glass, each with identical leadwork. The glass on the outside is clear and insulating, whereas the glass on the inside is painted, decorative, and has small gaps around the edges of each light (section of glass), to allow air flow.

Here, at the end of the walkway, my entire field of vision was filled with the stained glass, the Godhead at the apex right before my eyes. I dropped to my knees, and gazed a while. But time moved on, and my guide was restless. Evening Prayer is soon. Evening Prayer. Consider the time. There’s so much more to see.

We began making our way back along the nave, pausing, often, to look down.

There, the chairs, fanning out to fill the nave.

There, the altar, awaiting the next service.

There, the great suspended Christ, seen from above, arms outstretched to take in the width of the nave, and all within it.

Finally, out we go; slipping, sideways, through the gap in the wall. The door, lifted, and sealed, leaves no hint of what sits behind it.

So on we go, upwards once more, in search of another unknown. And what an unknown! Because above the ringing room is the clock room… and it’s the strangest clock room I’ve ever seen.

I cannot believe I am typing this, but high up in the tower of Southwell Minster, there is a tiny wooden cabin. A cabin inside a room. A cabin with doors, and windows, and even a little flat roof.

If you go up to the cabin - carefully, minding all the bell ropes that stretch from floor to ceiling - and open the door, you will find that the cabin contains one, very specific thing. The clock mechanism.

Why is the clock mechanism housed inside a little log cabin that has, inexplicably, been constructed in a room that’s halfway up a thousand year old tower, you ask? My friends, I wish I knew. It’s unhinged. I love it. I hope the clock feels very cozy and safe in its little house.

From the cabin, the clock sends out a single shaft, which turns the hands on the clock face. Here it goes, through the narrow passageway that runs around the room, and out the wall:

What an odd little set up. I don’t really know what else to say. Here’s some Victorian graffiti that’s also in the room, I guess…

Right, let’s climb again. Up to the bells!

There’s thirteen bells, all told, with the mechanism well kept in a fetching shade of red.

I don’t know much about bells, and time is running out, for this adventure, so let’s go on one final climb. Up, up, up.

The rattle of an opening door. A gust of air. After a long climb, with many stops, we finally spill out onto the roof of the central tower.

Up here it really becomes clear how pastoral a setting this is. How strange and incongruous to have a Cathedral out here, among the fields and farms. The great towers lifting up to God without a tower block for miles to compete. How enormous and impossible this would have seemed a thousand years ago. How enormous and impossible it seems, even now.

Gulp in the fresh air. Hear the distant cars, the voices floating up from the vast grounds surrounding the Cathedral. Consider the history of this place. This little town that’s seen the construction and destruction of a great palace, the downfall of a Cardinal, the arrest of a King. There’s much hidden in this sleepy corner of England.

But the clouds are promising more rain, and it’s time to descend; down through the staircases, and vast hidden rooms.

Down through narrow passages, past round windows and ancient carvings.

The evening is drawing in, the light trickling away, even as we descend.

Among the darkened stone of a Cathedral closing down for the end of day, the angels glimmer through the gloom.

But over to the east end, where the lights are still on. It’s time for evening prayer, then a little look around, before night falls completely.

There’s something about having a cathedral to yourself, after closing. The soft scuffing of boots on stone lifts up above distant echoes, as I head to the chapter house, alone.

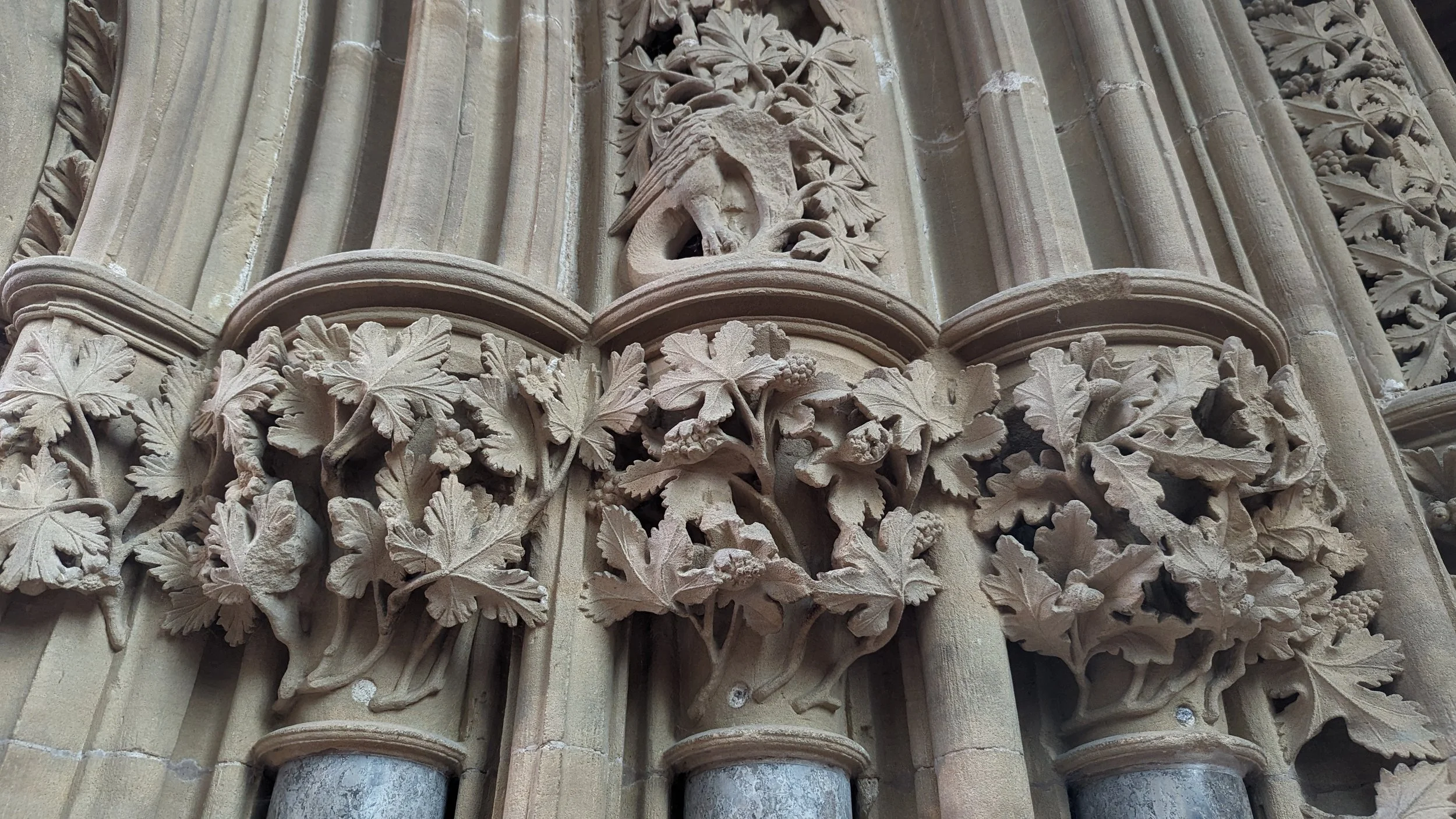

Built in the late 1200’s, the chapter house is considered the jewel in the crown of Southwell, and the carvings here are wondrous. The work here is regarded to be the best naturalistic stone foliage in the country, if not Europe. And dotted among the plants, little creatures.

For a moment, it’s almost as if the walls could come to life, soft leaves and strong stems uncurling themselves from the columns and trailing across the floor. Berries and buds ripening, opening, colour flushing across the stone; greens and reds and purple berries amidst the pale rock.

Come closer; come closer and see…

There’s dark shafts of purbeck marble here, too. Each white fleck a fossil, millions of years old; stone creatures placed amidst this stone forest.

There are so many more carvings, but night is falling. There’s only so much longer I can outstay my welcome.

Let’s slip through the nave, take one last look at the gilded Christ, suspended above the altar, the ceiling above, where we took our walk.

There is so much more to show you, but no more time. You must go, yourself, if you can; see the rood screen, the green men, the Dragon Stone. All these wonders I have not shown.

The sun is setting as we head outside, turning the wispy grey clouds a dusky pink.

I hope you can come here, some day… I hope you can come.

Poem of the Post

Cathedralsong

By Jay Hulme

It is night and I am watching the Cathedral;

like an avid twitcher, I identify every wing.

Look! There she sits - see the shadows of the

floodlights, the curved details; that romanesque

flourish, splicing into gothic, into grandeur, into…

gone.

She’s flying into dreams again, each stone

a compendium of prayer. First formed

by the hands of men long dead, yet still

she speaks; song and silence synthesised

into the sound of the sacred. She is

an instrument of interpolation; an organ

built entirely of time - each life that is lived

adds syllables to centuries of song.

Like any good twitcher, I see by silhouette;

move slowly, so as to not scare her off.

Listen closely, now - each Cathedral sings

with a slightly different sound.